Rock Sharpe

My Granny's Depression-era Glassware, where it came from, and what do we do with the things that come our way.

Would you believe that the origins of this essay began in late 2020? Actually, to be more precise, it began in early 1999 when my Grandma passed away at the age of 94 and I was told to box up her “crystal” and put it away some place because it was nice and I’d want it when I was older. I was likewise told to keep her wedding china — Krautheim’s “La Princesse” — a simple cream pattern with a rippled “rope” rim in a gilt stripe that is absolutely scratch-free because, like the crystal, it was never actually used, just displayed in the glass-fronted hutch in my Granny’s dining room. Use the good plates? For family occasions? Absolutely not.

While I don’t use the china much, the small dessert plates are the perfect size for cocktail party nibbles, so those were deemed useful. The crystal, however, was individually wrapped in packing paper, laid down side by side in a box, and put away in the back of my storage space. They stayed there for the next 21 years.

One of the projects I took on in late 2020 (weren’t we all looking for projects during lock-down?) was to clean out and re-organize. I decided to store the china because when had I last hosted a proper dinner? Wine and cocktails, however? That used to happen rather often and I’d hoped it would again. I then decided I’d dig out the box of crystal because of that overall 2020 feeling of if we’re going to die because of a mysterious airborne virus, maybe we should at least enjoy ourselves and use the good stuff while we’re here. I suppose I also wanted them as a talisman, a wish, if you will, for future gatherings with friends.

It was early December when I opened up the crispy paper that hadn’t been touched in decades. I thought of the young woman I was in 1999 when I’d packed them away and it made me wistful as nearly everything did at the time. The glasses emerged one by one and they were beautiful — delicate, whimsical, but I had no memory of them. No trademark anywhere, I consulted Replacements.com where they suggested doing a rubbing of the pattern so they could look up the make and style. The consultant at Replacements came back with a short note that led me down a rabbit hole of research which still gives me a bit of a thrill. It turns out Granny’s crystal isn’t crystal at all, but cut glass. It isn’t exotic or European, but American-made.

Okay, a quick 101: crystal is made of glass that is reinforced with a metal alloy (such as lead) which enhances its clarity and durability. This durability makes it better-suited for finer, more intricate cut-work. Along with the clarity, this creates beautiful light refraction and a “refined” look that is also less likely to chip. So, while the actual glass-cutting techniques can be the same, the base material will impart a different aesthetic. The base material of crystal also costs more.

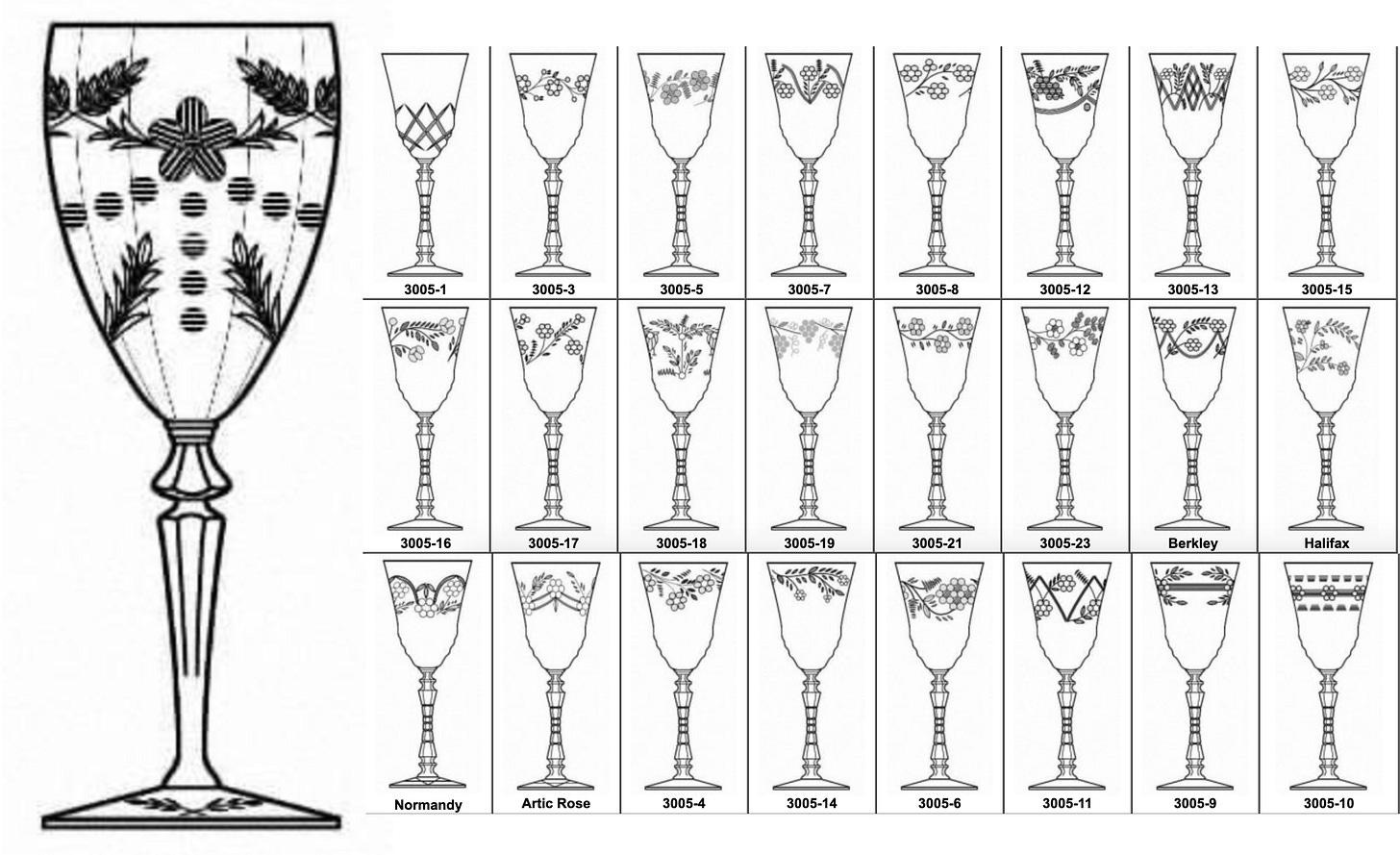

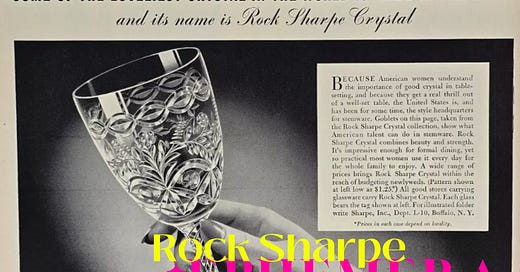

Replacements.com were well-familiar with the pattern I’d sent over, immediately identifying it as the “Granada” pattern from Rock Sharpe. The consultant explained that Rock Sharpe was a brand from Buffalo, NY that specialized in cut glass glassware in the early 20th Century. Digging deeper, I learned that Rock Sharpe was a subsidiary of the Cataract-Sharpe Company, founded by Alfred H. Sharpe in 1914. Sharpe purchased glassware blanks from Libbey Glass (also of Buffalo) and employed European glass cutters, mostly German and Czech, to design and decorate them. Actually, they only purchased ONE blank: stem line #3005, which Rock Sharpe used for ALL of it’s designs. So while the shapes could change, every Rock Sharpe glass had the same stem.

Note: While some may call Rock Sharpe “Depression Glass”, and yes, the blanket term does fit, it’s not exactly accurate. Depression Glass while sometimes clear, was mostly colored in shades of pink, green, amber, yellow, and blue. While it was available to buy, it was usually distributed for free as a promotion: Quaker Oats and other CPG brands would sometimes put a piece of glassware in a box of product as an incentive to buy. Crazy, I know. Can you imagine? People would collect and trade pieces accordingly. Manufactured in the Ohio River Valley (southwest of Buffalo, but not too far,) Depression Glass was of a lesser-quality than its Libbey Glass/Rocke Sharpe counterparts. Importantly, Rock Sharpe only cut from clear Libbey Glass blanks.

By the 1930s, Cataract-Sharpe had developed their “Rock Sharpe” collection and marketed it to Depression-era housewives in nearly every department store in America. The marketing backed this up by specifically targeting new brides and young homemakers of the 1930s, offering up Rock Sharpe as an affordable “dupe” for finer crystal. They also touch on the power of word-of-mouth, and the presumably female instinct to gossip about and among friends.

“Every Bride’s A Decorator at Heart! That’s why they love the authentic designing of Rock Sharpe Crystal, created in patterns of all periods and trends.”

Carol: “Sue has the girls livid with envy over her Rock Sharpe Crystal.”

Marcia: “Why my dear, anyone could afford it. Cost is very moderate.”

Prices were very moderate, with stemware costing between $0.85 to $3.00 depending upon the design complexity. I’ve never been able to find a price list or an advert that featured the “Granada”, however. Replacements says the pattern launched in 1936, which makes sense as my grandparents were married in September of 1937. That said, I’m not even sure they were a “wedding” gift or purchase. These could have come along any time in the next few years. I often wonder why my Granny chose the pattern; it’s feminine, floral, and romantic — an interesting choice for a very no-nonsense woman who, as the eldest of 4 sisters, had to forego her acceptance to Cal to go to work to support her family at 18. These glasses were something ladylike and whimsical, something precious and beautiful for her new home that she would be proud of for years. I think she went all-in on the indulgence and picked something just for herself.

As my Granny would tell it: “We didn’t have any money so we went to Reno.” This is only partly true; my Grandmother worked as a secretary to a C-suite executive at Wells Fargo Bank, while my Grandfather had already been defense attorney with well-paying clients for 10 years. But, it was probably prudent to NOT spend money on things like crystal in 1937, and instead make sure you could pay rent should something happen. So, they eloped to Reno. As the unofficial keeper of family photos I can say that there are none of their wedding, but there is a lovely snapshot of the two of them on a beach at Lake Tahoe (likely at Cal-Neva Lodge) at that same time. I never saw this photo until about 8 years ago — long after my grandparents died — so I’m only guessing when I say it was a honeymoon photo, but the dates align.

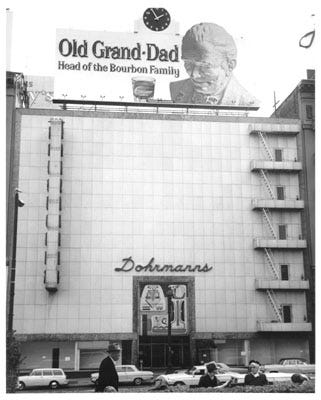

When I mentioned the Rock Sharpe glassware to my mother, she said “They probably got them at Nathan-Dohrmann’s…” Um…what? Where? Another deep dive, this time into the intricate histories of San Francisco department stores — a subject I’d mined plenty but had never once heard of said “Nathan-Dohrmann’s”.

Once upon a time in San Francisco, a Mr. Blumenthal opened a small “crockery” business in 1850. He sold it in 1858 to a Mr. Hersch, who died in 1862 when the company was acquired by a Mr. Nathan. In 1868 a Mr. Dohrmann came along, joined forces with Mr. Nathan, creating Nathan-Dohrmann & Co.. Phew!

With a focus on small homewares: china, crystal, glassware, clocks, lamps, and “art goods”, the store moved from its home at Kearny and Sacramento Sts (the heart of Gold Rush San Francisco), to eventually join the hodgepodge of retailers that formed The Emporium on Market Street in 18961. The store then went out on its own, moving to a large building on Bush Street until it was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire. Luckily, the company records were preserved, and the brand re-opened, along with most of the city’s retailers, on Van Ness Ave.

The next locales are a bit unlcear, but some point they expanded into the Nathan-Dohrmann building at Geary and Stockton Street, growing their product offer to include furniture and appliances including refrigerators and radios. They remained until the building was purchased by the I.Magnin company and demolished to make way for Timothy Fleuger’s Streamline Moderne store in 1944. Dohrmann’s (as it was called then), moved just down Geary Street to a smaller, more modern building facing Union Square.

Dohrmann’s definitely targeted the middle-class housewife, offering quality and values for those who may not have been able to afford the items over at Gump’s or I. Magnin. But, you’d never be embarrassed to have a piece from Dohrmann’s in your home.

Ultimately, Macy’s bought out the Dohrmann’s store on Geary Street in 1967 to develop the property into the building that stands today. While there is still a hospitality/hotel division of Dohrmann’s, the retail stores were acquired by Broadway-Hale, which was then acquired by Federated Department Stores in 1995…along with everyone else.

During the LA fires earlier this year, an image circulated of a swimming pool filled with 5 sets of china submerged on the pool steps, thereby saving the china from the fire. Turns out, this photo is actually from 2018 during the Northern California fires, but it’s a cool story. I shared the photo with a friend who replied:

“I currently have four generations of china collecting dust in my garage right now so as far as I’m concerned, let it all burn…I currently have a soup terrine from 1895. When, I ask you, will I be serving soup formally to a crowd?”

She had a point. We went on to discuss how women in their 40s are the “keepers of the shit” with parents who are reaching an age where they want to give away everything and seem to be handing you something every time you see them. What are we to do with it all? My friend went on:

“Where is the support for women who have generations of upper middle class collections and art to deal with? I’m not rich enough to have all sorts of people deal with this…and yet here it all is, of alleged value and importance and excellent taste, and I want none of it.”

It’s true. Our demographic has the burden of being the stewards of beautiful things; objects of art and utility that we no longer have use for, cannot store, don’t really want to use, and while they are all valuable, they generally won’t sell for anything close to their worth. Either our modern lives don’t require them, or their beauty and utility just doesn’t outweigh the fact that there’s no longer space for them. A set of china you use maybe twice a year? In a two-bedroom apartment? These beautiful things hold history, tradition, and sentiment, but…they’ve been thrust upon us without preamble or preparation. What are we to do with it all? I love collections, but I don’t love clutter. I love some of the things that have been handed to me, but most I could do without.

I don’t have any answers here, but I do know that these things tell wonderful stories of times when they were useful and beloved and even hoped-for: the small indicators of success and affluence that fueled the middle-class American dream. I’m not sure what that is in 2025, but to a young married couple in the mid-1930s perhaps it looked like a nice set of glassware that could maybe, possibly, be given to a granddaughter.

Now that they’re out of storage and happily snug in my cabinet, the Rock Sharpe glasses are a part of my regular entertaining. The coupes are great for cocktails and Champagne, and the goblets are small but generous enough for any kind of wine. The oyster glasses are the mystery — originally meant to serve individual portions of seafood (an oyster cocktail, shrimp cocktail, or I suppose ceviché,), these were also used for fruit salads or small desserts. I have no idea what to do with them, but maybe I will one day. Either way, they are both useful and used often.

Objects, like people, come in and out of our lives for some reason or another. It took me 21 years to open a box to consider these glasses and start learning about them. Other objects have been handed to me over time that don’t hold nearly the same interest or fascination for me, but maybe that’s the point? Maybe we keep the things that resonate and shed the rest? It’s hard to say. Rock Sharpe may not be as valuable as Baccarat, but the story behind it and how it came my way certainly means something to me, and I think of it every time I use them.

Hitz, Anne Evers “Lost Department Stores of San Francisco”, 2020. Page 131

That was an absolutely fascinating description of your Granny’s Rock Sharpe glassware. I can only imagine the thrill of discovering these beautiful cut glassware after they had been sitting in your storage locker for over 21 years!

Your diligent research to discover their identity was quite remarkable as well as very interesting.

I know your Granny would be so pleased that you are using everyone of them… such a priceless treasure for you to use and remember her.

I especially loved those fantastic old photos of your grandparents at Lake Tahoe. It added a very special personal touch to your story. I am sure that you must think of Joe and Ida every time you use these!!

I agree, that you look like your beloved Granny!

Exceptional post. Thanks for sharing memories and teaching me new things too. (Also, I think you look like your grandmother!)