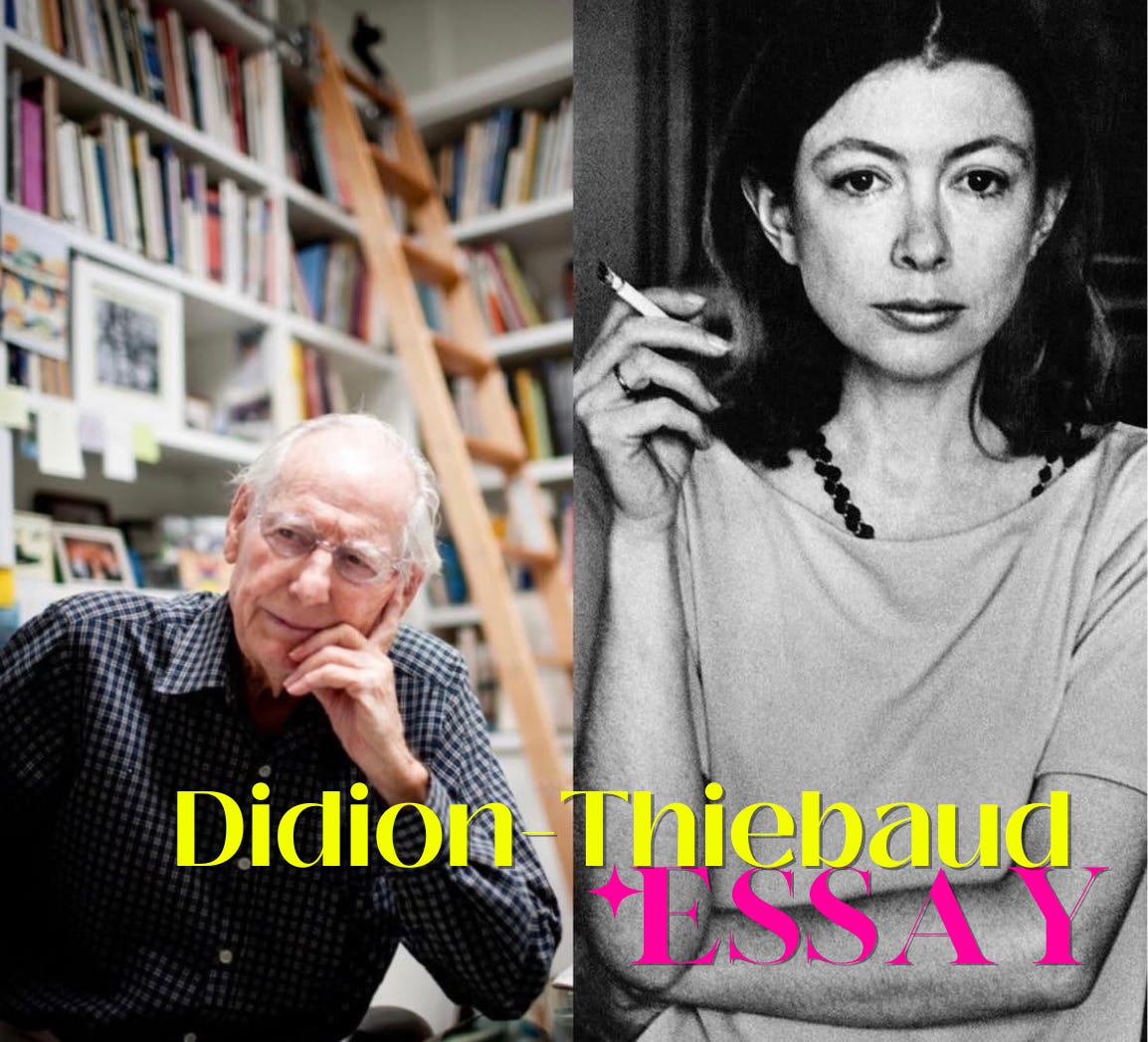

This morning I was reminded of this post I’d written in 2021 when two of my creative heros, Joan Didion and Wayne Thiebaud, died within days of each other during Christmas week. Reposting here with a few updates…

On the morning of the 23rd I was in my parents’ guest room in Napa reading the headlines when I saw the news. I went into the kitchen and told my Mom in her pink bathrobe: “Mama, Joan Didion died this morning.” I heard her sigh. On the morning of the 26th I was in an Uber heading home to San Francisco when art collector Stefan Simchowitz posted one of Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings to his Instagram with an “RIP”. I started crying behind my sunglasses and hoped the driver wouldn’t think I was having a crisis.

Didion, Sacramento-born, and Thiebaud, Sacramento-settled, crafted in different mediums, but with similarities. Both created indelible images — one in words, one in paintings and drawings. Economical, simple, clear — like the bright, hot central valley sunlight that flattens every image but leaves subtle contours. There is a coldness or even sadness to their work that most don’t notice because they don’t look past the image: the overly-clean glass case housing Thiebaud’s frosted cakes, or the way Didion talks about a “new dress” and you know the story will end in a disappointment. They were serious and controlled, both in their presentation of themselves and in their work. Behind their reserve, both were witty, kind, loving people who enjoyed a laugh. Both thought and over-thought and planned and fretted over minutiae, but the results were always fresh and contemplative.

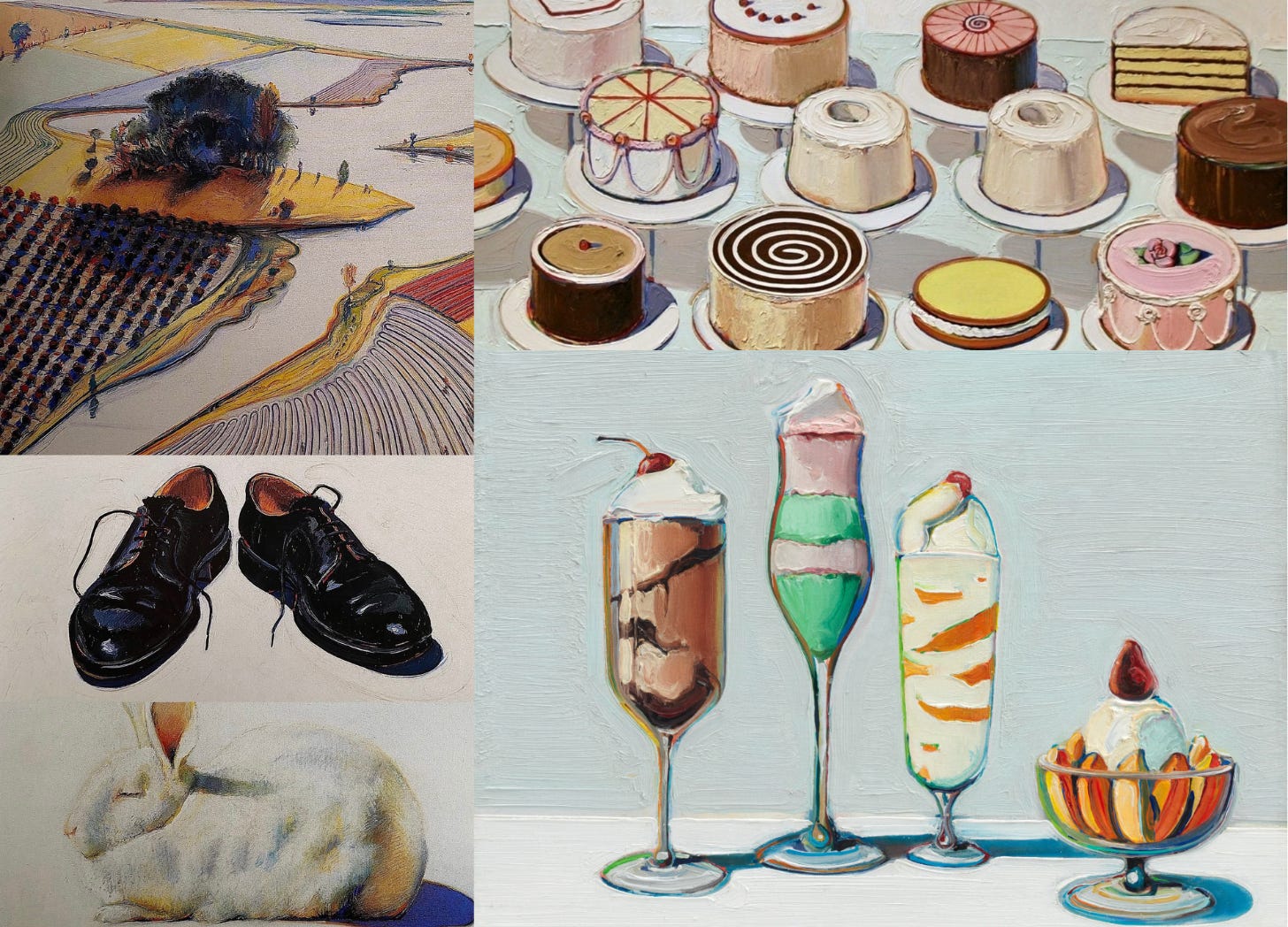

Growing up in San Francisco it wasn’t uncommon to go into someone’s house and see a Thiebaud painting or sketch on a wall - usually in his favorite sanguine pastel. So it seemed natural to go to UC Davis and try to learn from him since I wanted to study art. An early color theory class showed us work from Thiebaud and it changed everything. How a pair of black shoes read as black but there are touches of bright red and yellow on their edges. Or how a white bunny rabbit in pastel is made up of pale lavender, yellow, and even dark purple in the coral pink of the ear. How a shadow is not merely gray, but a darker shade of the color it is. There are hot colors where there should be cool colors, and cool colors in exactly the place where the light hits. This made me laugh with delight at first, and then I realized it was brilliant and frightening to see this way. Didion’s writing, which I’d first discovered in a California literature class at Davis, left the same impression of frightening brilliance. How simple, how lovely, how perfect, how terrible.

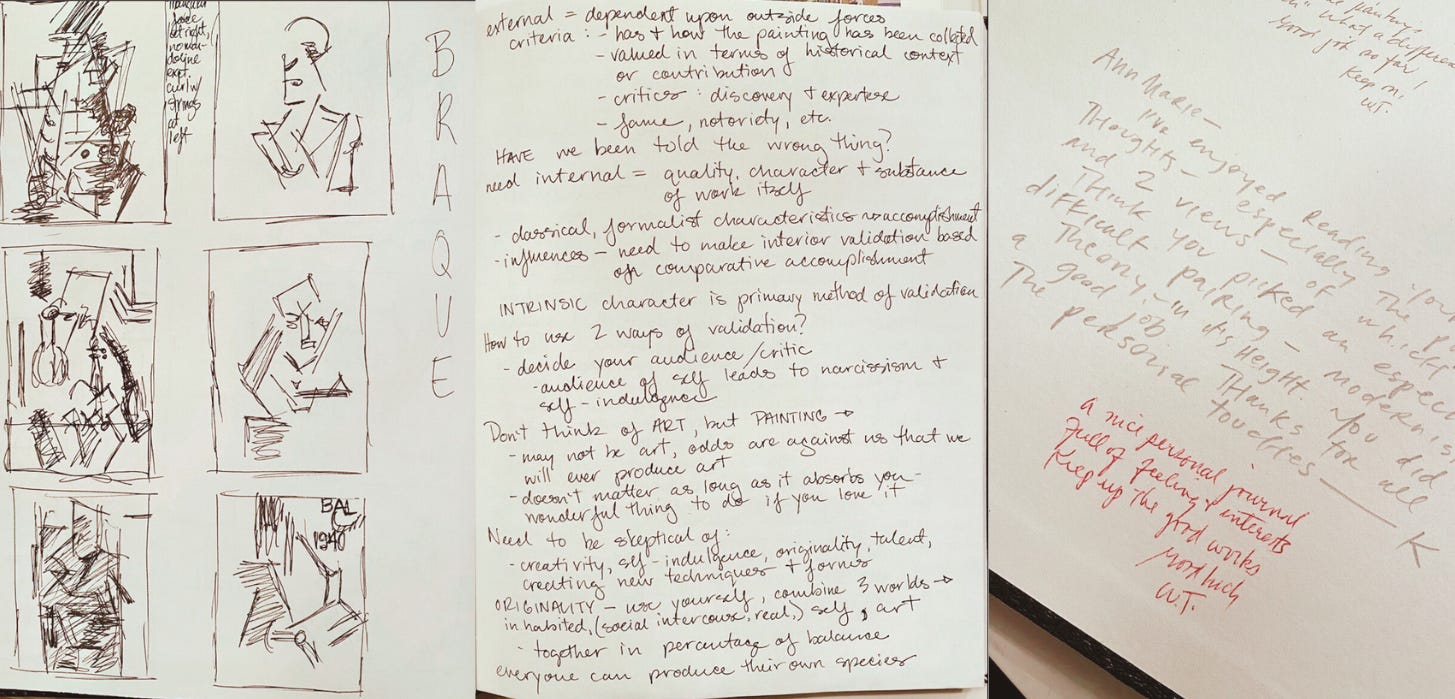

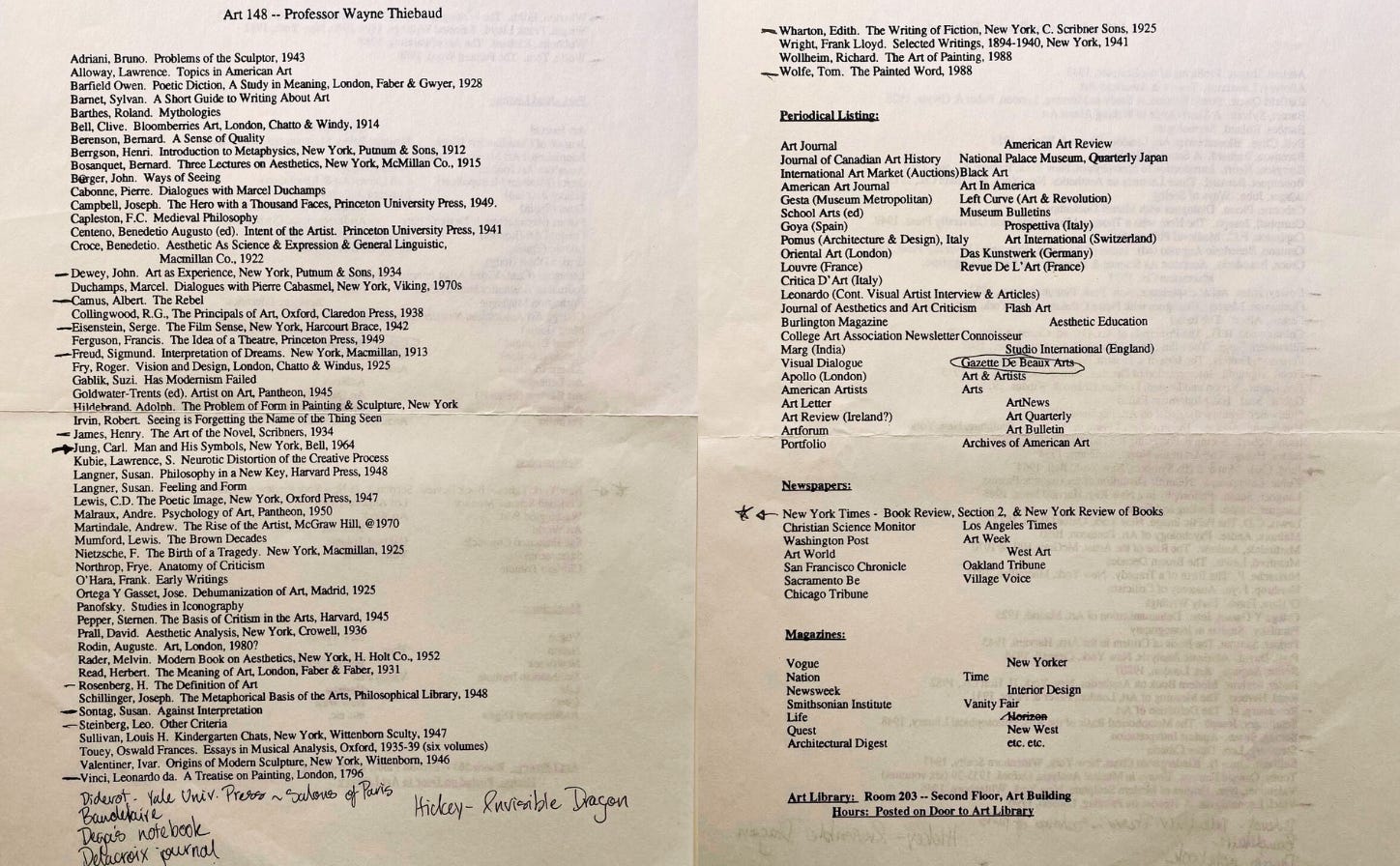

Both impressed upon me the habit of keeping a notebook. Thiebaud insisted on it when I finally got to take his class, Art 148 - Theory & Criticism. We were to keep an unlined notebook of class notes and papers, all hand-written; unlined so we could make thumbnail sketches of the lecture slides, and practice quick sketching. Thiebaud also suggested we start collecting postcards of different art works and different cultures, because “more things from different cultures make us understand anatomy of human beings.” At least that’s what I have written down in said notebook. I have never stopped my habit of writing in unlined notebooks. Likewise, I have never stopped my habit of collecting postcards, especially art postcards. I know the internet makes image searches easy, but there is nothing like a perfectly photographed and reproduced art postcard you can keep. They are all over my house - framed, kept in boxes, shoved into books.

Wayne’s class was mind-blowing. He would arrive in a navy blazer and bow tie most days, and would spout all kinds of contemplative ideas. “Visual power sustains joy,” “aesthetic experience is apart from function; [there is an] eternal relationship in forms,” “paintings are flat, still and silent - animated only by you and your physical empathy,” and when discussing art: “know why you like it - specifics of engagement encourage a kind of dialogue”. When I read through this class notebook from 1996 for the first time today I couldn’t believe it. (I also couldn’t believe I’d hand-written 4 ½ pages for my final paper on modernist theory, comparing Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. I’d even thrown in a bit of Samuel Johnson’s dialogue from “Rasselas”. What an insufferable 19-year-old jerk I was.) Wayne would sometimes rush through slides of art to test us on how quickly we could sketch them, or other times would just play recordings of Fats Waller, The Beatles, or Mel Brooks’ “2000 Year Old Man”. Even looking at an image upside down was encouraged. It all could generate the kernel of some kind of something.

At one point I asked Wayne to sign an SFMOMA poster I had from the reopening in 1996. He drew a small heart and signed his name. I asked him about the heart and he said “well, a heart is really just an upside-down W…”

The idea of “upside down” was big with Wayne. He’d give entire lectures were the slides were flipped so that we could all see how a great work should still work that way. That is, it’s balanced, compelling, and the right elements still hold focus. This was also his recommendation when our own studio work maybe wasn’t coming together: “Have you tried turning it upside-down? If you do, you’ll see what’s wrong.” When the Legion of Honor museum held the Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art exhibit earlier this year, I was so pleased to see mention of his love of the upside-down. This was a fantastic show that included Thiebaud’s work as well as pieces from his vast and impressive art collection that he used for inspiration. He loved art in dialogue and this show captured that.

Joan Didion’s kernels come to me all the time, and every so often I’ll pull down Slouching Towards Bethlehem or The White Album and bring the images back to me. The opening sentence of The White Album, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” gives you the message and the question immediately: the human experience requires some distillation into language. Maybe it’s the truth, but more often than not it will be something else and you may never know which one. Her own storytelling is so entrancing, yet always leaves me with the sensation of having just been sucker-punched.

I always come back to her paragraph about the Manson killings and I still find it to be one of the best paragraphs ever composed in the English language. It’s a memoir, an atmosphere, a point of fact, an inevitability, an ending and a beginning. Simple, elegant, utterly terrifying.

“I recall a time when the dogs barked every night and the moon was always full. On August 9, 1969, I was sitting in the shallow end of my sister-in-law’s swimming pool in Beverly Hills when she received a telephone call from a friend who had just heard about the murders at Sharon Tate Polanski’s house on Cielo Drive. The phone rang many times during the next hour. These early reports were garbled and contradictory. One caller would say hoods, the next would say chains. There were twenty dead, no, twelve, ten, eighteen. Black masses were imagined, and bad trips blamed. I remember all of the day’s misinformation very clearly, and I also remember this, and I wish I did not: I remember that no one was surprised.”

-Joan Didion, The White Album, 1968-1978

I am constantly chilled by the dogs barking under an eternal full moon, and often ponder the terrible irony of “misinformation very clearly.” Didion’s telling of August 9, 1969 is a prose post-mortem of the free love era, surgically precise and efficient, hinting at a lost innocence we still struggle to understand.

It’s the indelible imagery in her writing that surfaces again and again for me. Her husband John writing D-U-S-T in the plentiful dust of her parents’ Sacramento home, or going to buy Linda Kasabian a dress at I.Magnin, or getting off the plane at Idlewild and realizing once touching down in New York that the dress you thought was chic in California was decidedly not in New York. (I feel this way every time I go to New York, even now.) That, of course is how her essay Goodbye to All That begins. An essay about New York and living there when you’re young.

“I began to cherish the loneliness of it, the sense that at any given time no one need know where I was or what I was doing.”

That, for me, is the best part of New York, but I have never had much desire to live there. Whenever I have a friend who is considering a move to New York, I scan a copy of Goodbye to All That and send it to them. One friend laughed and decided not to go. I mentioned it to another friend recently but forgot to send it her way. She came over for dinner and I pulled it down and handed it to her to look over. “Can I take this home?” I wanted to say yes, but insisted she should have her own copy to keep. “Sorry - I love you, but Joan Didion does not leave this house.”

I really love this. I don't think I knew you studied with Thibaud!